The Battle of Issus: When a Hoplite Spear beat a Phalanx Pike (or when bigger wasn’t better)

It did not happen often, but in the right circumstances (at least from the hoplite point of view) the Greeks with their short spears were able to hold their ground and repulse the Macedonians with their much longer pikes. That is exactly what happened at the Battle of Issus in November 333 BC.

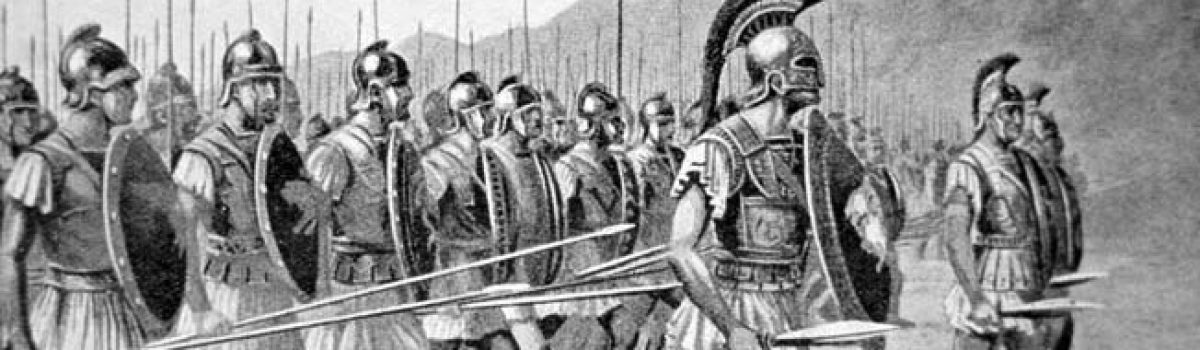

The Macedonian phalanx with its 16-foot-long pikes (or sarissas as they called them) normally has a definite advantage over a traditional Greek hoplite phalanx (or shield wall) with their 8-foot-long spears. At least that is true on flat, open, solid ground. While such a parade ground-type battlefield was preferred by either, the hoplites proved on at least two occasions to be more flexible and more adaptable when the lay of the land was less than ideal. The first was at the Granicus, in 334 BC (as described in chapters 21-29 of Throne of Darius: A Captain of Thebes). The second was a year later at the Pinarus River – also known as the Battle of Issus.

At the Issus, the Persians posted 10,000 Greek mercenary hoplites at the center of their line, with about the same number of kardakes (similar to Greek peltasts; e.g. lightly armored medium infantry who fought in formation with shield and spear as well as bow) to either side. The Greeks were under the command of Thymondas (a nephew of the late imperial general Memnon of Rhodes) and Amnytas – a Macedonian exile. Amnytas and his father, Antiochus, had served Alexander‘s father, Philip, with distinction, but had a falling out with Philip after his victory over the Athenians and Thebans at Chaeronea in 338 BC. (This Amnytas is not to be confused with Amnytas, the son of Perdiccas, who fought for Alexander).

Opposite the hoplites were five of the tough Macedonian phalanxes, the brigades (from right to left) of Coenus, Perdiccas, Craterus, Meleager and Ptolemy. To their immediate right, Alexander stationed his elite Hypaspists – later known as the Silver Shields, and to their immediate left he had placed yet another phalanx, the brigade of Perdiccus’s son, Amnytas. These forces on the flank would charge across the Pinarus River and scatter the kardakes while the pikes would attack and break the hoplites. That, at least, was Alexander‘s plan – and what he and his generals expected would happen.

But it did not go that way. (As will be shown in the second novel in the series: Throne of Darius: A Princess of Persia.)

The Pinarus was not a particularly deep river – more of a stream, really, but like the Granicus the year before the Macedonians would have to wade through its muddy, slippery course and then fight an uphill battle against an enemy on the farther – and higher – bank. The first time the Macedonians charged, they were thrown back. They reformed, however, and went back across – but fared even worse the second time. Not only did the hoplite shield walls hold, but the Greeks actually counterattacked and drove the Macedonian phalanxes back across the river. They hoplites were able to get in among the jumbles, disorganized mass of pikes. They forced the pikes aside with their shields and got in among the Macedonians with their spears and short swords. The pikemen, who needed both hands to hold the long, heavy sarissas, were unarmored, without shields and had only small daggers as a secondary weapon. They fought back fiercely, but faced with armored, shield-bearing, sword-wielding Greeks were forced to retreat. The hoplites similarly pulled back and reformed at the top of the bank.

Unfortunately for the valiant Greeks, Alexander and his cavalry had sliced through the Persian left and then swung about behind the kardakes on the hoplite’s left flank. Caught between the elite Hypaspists and the heavy cavalry, the kardakes broke, and left the hoplites flank and rear unprotected. Alexander then proceeded to roll up the hoplite line just as his phalanxes made their third charge across the river.

The hoplites, however, did not break. They fell back and covered the retreat of the rest of the Persian army. But they paid a heavy price; 8,000 of them died on that field. Amnytas was able to extract only about 2,000 men – whom he managed to get safely to the coast and in a Dunkirk-like move took them off safely to Cyprus. From there he took most of them to Egypt, while others either went home or later returned to the mainland, to fight against Alexander on the flat plain of Gaugemala (which will be included in the third book in the Throne of Darius saga).

Comments (2)